#7 - Unsafe by Design

How social interfaces ignore the female user base, perpetuating harassment and inequality

(TW: Mention of sexual harassment and abuse)

About a month ago, yet another feminicide occurred in Italy: after one week of frantic searching by the authorities, 22-year-old Giulia Cecchettin was found murdered at the hands of her ex, Filippo Turetta, who had attempted to flee the country to avoid the authorities. While it wasn’t the first nor the last gendered-related murder in the country1, the case got a lot of media traction and (thankfully) caused a major upstir of feminist movements and discussions within Italy.

When I read about Giulia’s tragic end, I was invaded by a deep feeling of anger, as well as frustration. Knowing that as women we are still being discriminated against in so many ways and that we are at risk of potentially losing our lives because of rape culture is something I suddenly found that I can’t stand anymore.

Feeling the urge to do something, I started by channeling said anger into educating myself more on feminism in general: not only to learn and share more about feminism and the consequences of inequality but also to help debunk any residue of internalized patriarchy I might have had. In my readings, I came across the book Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez, which extensively describes gender bias in data collection. As Angela Saini states in her review of the book,

[…] women must live in a society built around men. From a lack of streetlights to allow us to feel safe, to an absence of workplace childcare facilities, almost everything seems to have been designed for the average white working man and the average stay-at-home white woman.

This made me reflect on my own experience and I quickly realized how this phenomenon can easily be found in tech as well. As a UX Designer with a trained eye for poor user experiences, I recalled a few episodes of digital products I used that showed how women are still invisible, even when said products are meant to cater to them as well.

Women’s data and privacy needs are invisible

“User would like to send you a picture”

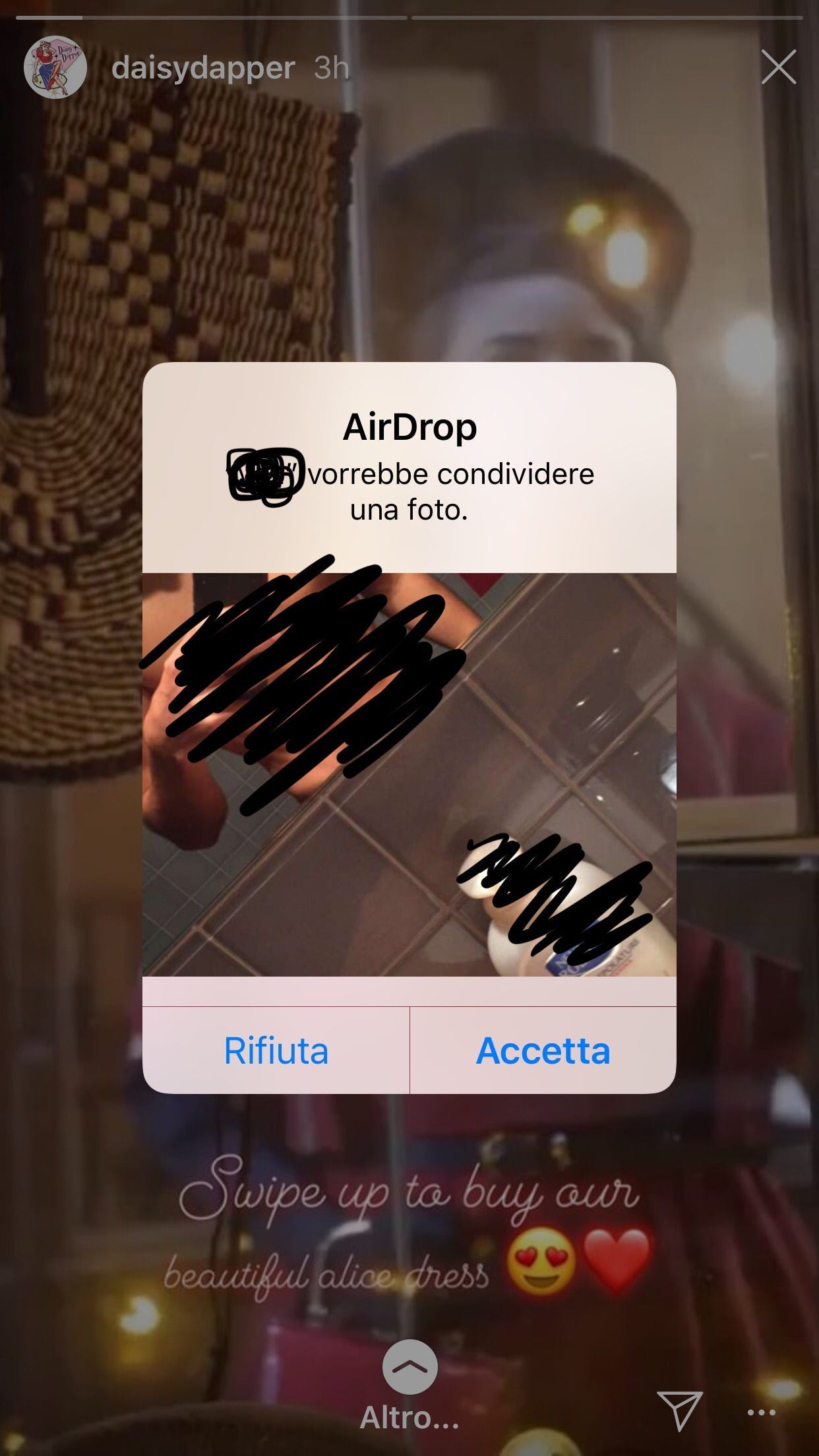

A few years ago, shortly before COVID-19 disrupted our lives, I was on my usual train commute back from work. While I was scrolling through stories on Instagram, an AirDrop notification blocked my actions on the screen:

A guy on the train had noticed me and deemed it appropriate to send me his shirtless picture via his iPhone. Startled, I immediately denied the AirDrop request. Not satisfied, he tried again a few times, and in between several clicks of the “Deny” button, I was able to take the screenshot shown above for safety reasons and reach the AirDrop settings to shut down this unwanted communication. As I then looked outside of the window and faked being absorbed by the scenery (which was actually pitch dark as it was past 6 pm on a winter day), I noticed a young man in the window reflection getting up and looking insistently in my direction. Thankfully, that was his stop and I never saw him again.

One of my first self-critiquing thoughts was “I should have disabled AirDrop from the beginning, duh!”. But if you look at it from a designer’s perspective, the AirDrop feature

Was opt-out instead of opt-in, which meant something like this could have happened to anyone who hadn’t manually disabled it in the settings, and

The underlying technology didn’t have a blocking system for inappropriate content.

I do believe that with AI the 2nd point could be achieved easily nowadays compared to those days, but what stayed with me was that in this scenario, the edge(?) case of AirDrop being used inappropriately and not being accounted for was what led me to experience fear and uneasiness in what should have been a quiet moment in my daily routine.

Telegram’s People Nearby

I became a daily user of Telegram back in 2016 when my developer friends introduced it to me, and was happily advocating for it versus using WhatsApp - editing and deleting messages, finally! My opinion of the app however quickly changed when they introduced the People Nearby feature in mid-2019: this feature allows you to see a list of users in your surroundings, and start chatting with them directly. I unknowingly opted in for this with a routine software update2, which led to me receiving unwanted chat messages (all by men) throughout my day.

While in other apps like Meta’s Messenger, any new chat with a stranger is put into a separate folder away from your main chat list, the off-putting thing about People Nearby is that the chats started by harassers are treated by the app as the normal ones, which feels a bit like having an unwanted guest appear in your own home. Again, I started fiddling with the privacy settings until my user wasn’t available via People Nearby anymore, and I hid all information from those who were not in my contacts.

As I would still receive random messages a few more times after this (not sure how, since I never publicly listed my Telegram contact information), I had to resort to deleting my username altogether. This still allows me to use Telegram to chat with friends and family, but my username, which at the time was a funny pun I was proud of, had to be deleted and that honestly pissed me off.

While I’m sure that the ideas behind the feature were noble (meeting new people, exchanging contacts more easily, etc.), a quick internet search shows that the People Nearby feature was not widely appreciated. Lifehacker wrote in 2021:

This opens users up to hacks, stalking, or worse—and Telegram as announced no plans to fix the problem3

While Telegram advertises itself as Private and Secure, the reality is:

Anyone can access your location if the People Nearby feature is enabled;

Anyone can start a chat with you and send you messages, until you manually block them, unless you remove your username altogether.

This isn’t the only upsetting thing when it comes to women’s safety concerning Telegram. Due to its features, the chat app is knowingly used in Italy by large groups of men who share explicit pictures of female partners, relatives, and kids - all taken without the subject’s consent. When a 19-year-old girl was assaulted by a group of male friends in Palermo last July, users within two groups of 12k and 14k members respectively started requesting the video of the assault filmed by one of the abusers. The reward? An exchange of private, explicit pictures of women and children in their own lives.4

So what now?

Telegram isn’t the only app with chat features that perpetuates harassment-type behavior. I’ve personally received unwanted requests on Instagram, Facebook, and even LinkedIn, and I’m sure other women like me can share similar stories.

I believe the first thing we need to do as tech makers in this scenario is recognize that:

Harassers and abusers exist, and they act on the web without remorse.

They are not “monsters” as the media often portrays them, but real people who go about mostly unbothered in society. Their sexist behavior is a byproduct of our patriarchal society and is therefore perpetuated by a large group of both men and women.

But, since women make up about 50% of the world's population and have every right to use digital products and services without fear for their safety,

Designers who create social interfaces must design against this scenario.

While there is no cookie-cutter solution for this situation, there are a few tools and activities we can do to help:

1. Use Anti-Personas

In the definition of Nielsen Norman Group, an Anti-Persona is “a representation of a user group that could misuse a product in ways that negatively impact target users and the business”5. If the product we are designing for deals with sensitive data and poses potential physical or emotional threats, creating Anti-Personas and using them to mitigate risks and threats can help both the users and the business.

2. Ensure equality in user recruitment as well as in the product team

If the majority of the users we involve in user research activities aren’t female, any potential pain points concerning women’s safety might not arise. The same goes in the workplace: if women are not involved in the making of a product that caters to them as well, they can’t bring their diverse perspectives not only in terms of safety but also for other aspects of the product as well. Gender equality can therefore be beneficial to all in this setting too.

3. Train AI tools to be gender-inclusive

A recent study that examined 13 AI-based chatbots revealed that many of them show gender bias both in the context of professional genders and in fiction, with ChatGPT-4 being the most biased6. If AI is truly the next revolution, we must address this quickly to avoid amplifying inequalities further.

And lastly, don’t forget to speak up against injustice, whether online, in the workplace, or elsewhere. I’d like to end this article on a positive note from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the author of We should all be feminists:

Gender as it functions today is a grave injustice. I am angry. We should all be angry. Anger has a long history of bringing about positive change. But I am also hopeful, because I believe deeply in the ability of human beings to remake themselves for the better.

~ Maria Teresa

209 women have been murdered in 2023 only, with 58 of them by their (male) partners or exes.

In Telegram’s current version, the feature has been moved within the app and seems to have switched from opt-out to opt-in.